[:en]The news we shared below was prepared for OutRiders by Seçil Epik on September 02, 2018:

“I grew up in a small town in Turkey. As a child, I loved playing football in the empty lots dotted around my neighbourhood. I was damn good at it too. But when I turned 11 or 12, my mother told me it would no longer be appropriate to play football with the boys. After all, I was developing breasts. I disobeyed and played in secret but, eventually, a game which made me feel so free and happy became off limits – all because of the gender others attributed to me.

My mum is not a conservative or religious person. She was simply reacting to the expectations of neighbours and society at large. She didn’t want people to speak ill of her daughter playing football with boys. Many years have passed since – seriously way too many, almost 20 years – and during them, I lost the bond with football and other sports. In my teenage years, I turned into a bookworm and studied literature at university. Discovering my homosexuality in my early twenties while at the same time discovering feminism and meeting the LGBTI+ community, to say the least, “changed my life.”

So from being a football player, I became a football sceptic. I began to see the game as a display of masculinity. But then, three years ago, I had a change of heart and started to play again. I joined a team whose very purpose was precisely shattering my perceptions: Atletik Dildoa. Playing with people who were looking for the same thing as myself allowed me better to accept my body and to feel free – just as I felt as a kid when society hadn’t got around to labelling me with a gender. So once again, the football field became my oasis of freedom.

I was not alone in the search for a refuge. Since 2014 the Istanbul Governor’s Office has banned the once well-attended annual Pride March. In the capital Ankara, a ban on all LGBTI+ events – film screenings, plays, panels, discussions or exhibitions – has been in force for nearly a year. Apart from these “official” bans, a plethora of activities in cities like Bursa, İzmir, Mardin involving the LGBTI+ community was denied authorisation. But there is still one event that allows some breathing space, one which also has a vital role in the fight against gender discrimination in sports: Queer Olympix.

we came up with an idea and got excited!

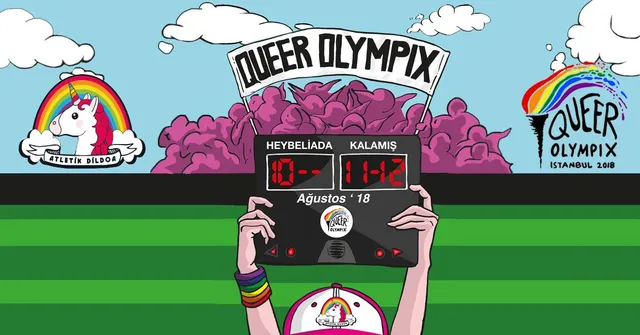

At Atletik Dildoa, we came up with an idea and got excited! We were going to break gender norms and make space for LGBTI+ to freely enjoy their favourite sport. With the support of Young Feminist Fund FRIDA, FARE (Football Against Racism in Europe) Network and the large municipality of Kadıköy in Istanbul’s Asian side, not to mention a lot of volunteer effort, Atletik Dildoa’s dream came true in 2017. This year, the second edition of Queer Olympix was organised from August 10 to 12 at the shore of Kalamış on the Asian side of Istanbul and the small island of Heybeliada off the city’s coast. Many new people joined us this year. It is safe to say the event has already become a “tradition” for queers in Turkey.

As its name indicates, Queer Olympix is a little bit different from the “Olympic Games” we all know. Ten teams, mostly composed of LGBTIs and women, compete in four different branches: football, beach volleyball, long jump and a relay race. To come first at Queer Olympix, you don’t need to be the team which scores the most goals, runs the faster or gives the best passes on the pitch. The most important rule is to enjoy sport without discrimination or facing hate speech.

There had been a very strong LGBTI+ movement in Turkey. So when the bans suddenly started kicking in, homosexuals and transgenders were among the first to feel the impact of a more authoritarian Justice and Development Party (AKP). Spaces for activism were heavily restricted. An LGBTI+ community, once at the forefront of the massive Gezi Park protests of 2013, became the target of ever more intensified repression. Thus, being able to organise an original extravaganza like Queer Olympix not once but twice, and to gather queers from across the country and even international guests shows how resilient and unwavering are the roots of the LGBTI+ community in Turkey.

football is more than just football

As in most parts of the world, football in Turkey is a male-dominated space where sexism and homo/bi/transphobia has become a norm. Although many women and LGBTIs enjoy the game, they feel excluded and become indifferent on time. Atletik Dildoa was created in 2015 by a group of people mainly like my younger self, who once enjoyed football but stopped playing. Atletik Dildoa grew into an autonomous space for sports where any age, gender and gender expression feel comfortable.

Everyone says “football is more than just a game,” but uttered by those who have been excluded from the field, the saying is more than just cliché. Queer Olympix provides members of the LGBTI+ community a chance to play sport but also allows them to socialise, become more visible and share experiences.

The proof is in the smiles and laughter of participants and the occasional spark in their eyes. A young teenager approached me at our information stand during this year’s Queer Olympix. She must have been 16 or 17-years-old. Lots of things were going on as she arrived to the outdoor sports complex. One group was playing volleyball on the beach, another was in the small football ground, training before the game. Still, others were attending yoga and juggling workshops. And those who were refraining from organised fun were enthusiastically dancing, enjoying being able to spend time with people like themselves.

She pointed at the rainbow flag and asked me what the event was about. I told her that it was a sports tournament held mostly by people who were homosexuals and transgenders, upon which she said: “I am a lesbian too”. She said it so genuinely that it sounded like the most natural thing in the world. I replied that she was welcome to attend the activities and even join the mixed team if she wanted. She was joyfully smiling as she left the stand. I am sure she will never forget that day, that crowd and the experience of seeing all the different expressions of gender together in the same space.

Queer Olympix has demonstrated the resiliency of the LGBTI+ community in Turkey. It is eliminating barriers to practice sport. But it is also telling the world that queers will not be excluded from public space. We may face restrictions. Political and social repression may prevent LGBTI+ groups from staging marches and celebrating Pride. But if we are not allowed to walk, we will aspire to run.

Photo caption: The second edition of Queer Olympix was staged between August 10 and 12 in Istanbul.”[:tr]The news we shared below was prepared for OutRiders by Seçil Epik on September 02, 2018:

“I grew up in a small town in Turkey. As a child, I loved playing football in the empty lots dotted around my neighbourhood. I was damn good at it too. But when I turned 11 or 12, my mother told me it would no longer be appropriate to play football with the boys. After all, I was developing breasts. I disobeyed and played in secret but, eventually, a game which made me feel so free and happy became off limits – all because of the gender others attributed to me.

My mum is not a conservative or religious person. She was simply reacting to the expectations of neighbours and society at large. She didn’t want people to speak ill of her daughter playing football with boys. Many years have passed since – seriously way too many, almost 20 years – and during them, I lost the bond with football and other sports. In my teenage years, I turned into a bookworm and studied literature at university. Discovering my homosexuality in my early twenties while at the same time discovering feminism and meeting the LGBTI+ community, to say the least, “changed my life.”

So from being a football player, I became a football sceptic. I began to see the game as a display of masculinity. But then, three years ago, I had a change of heart and started to play again. I joined a team whose very purpose was precisely shattering my perceptions: Atletik Dildoa. Playing with people who were looking for the same thing as myself allowed me better to accept my body and to feel free – just as I felt as a kid when society hadn’t got around to labelling me with a gender. So once again, the football field became my oasis of freedom.

I was not alone in the search for a refuge. Since 2014 the Istanbul Governor’s Office has banned the once well-attended annual Pride March. In the capital Ankara, a ban on all LGBTI+ events – film screenings, plays, panels, discussions or exhibitions – has been in force for nearly a year. Apart from these “official” bans, a plethora of activities in cities like Bursa, İzmir, Mardin involving the LGBTI+ community was denied authorisation. But there is still one event that allows some breathing space, one which also has a vital role in the fight against gender discrimination in sports: Queer Olympix.

We came up with an idea and got excited!

At Atletik Dildoa, we came up with an idea and got excited! We were going to break gender norms and make space for LGBTI+ to freely enjoy their favourite sport. With the support of Young Feminist Fund FRIDA, FARE (Football Against Racism in Europe) Network and the large municipality of Kadıköy in Istanbul’s Asian side, not to mention a lot of volunteer effort, Atletik Dildoa’s dream came true in 2017. This year, the second edition of Queer Olympix was organised from August 10 to 12 at the shore of Kalamış on the Asian side of Istanbul and the small island of Heybeliada off the city’s coast. Many new people joined us this year. It is safe to say the event has already become a “tradition” for queers in Turkey.

As its name indicates, Queer Olympix is a little bit different from the “Olympic Games” we all know. Ten teams, mostly composed of LGBTIs and women, compete in four different branches: football, beach volleyball, long jump and a relay race. To come first at Queer Olympix, you don’t need to be the team which scores the most goals, runs the faster or gives the best passes on the pitch. The most important rule is to enjoy sport without discrimination or facing hate speech.

There had been a very strong LGBTI+ movement in Turkey. So when the bans suddenly started kicking in, homosexuals and transgenders were among the first to feel the impact of a more authoritarian Justice and Development Party (AKP). Spaces for activism were heavily restricted. An LGBTI+ community, once at the forefront of the massive Gezi Park protests of 2013, became the target of ever more intensified repression. Thus, being able to organise an original extravaganza like Queer Olympix not once but twice, and to gather queers from across the country and even international guests shows how resilient and unwavering are the roots of the LGBTI+ community in Turkey.

Football is more than just football

As in most parts of the world, football in Turkey is a male-dominated space where sexism and homo/bi/transphobia has become a norm. Although many women and LGBTIs enjoy the game, they feel excluded and become indifferent on time. Atletik Dildoa was created in 2015 by a group of people mainly like my younger self, who once enjoyed football but stopped playing. Atletik Dildoa grew into an autonomous space for sports where any age, gender and gender expression feel comfortable.

Everyone says “football is more than just a game,” but uttered by those who have been excluded from the field, the saying is more than just cliché. Queer Olympix provides members of the LGBTI+ community a chance to play sport but also allows them to socialise, become more visible and share experiences.

The proof is in the smiles and laughter of participants and the occasional spark in their eyes. A young teenager approached me at our information stand during this year’s Queer Olympix. She must have been 16 or 17-years-old. Lots of things were going on as she arrived to the outdoor sports complex. One group was playing volleyball on the beach, another was in the small football ground, training before the game. Still, others were attending yoga and juggling workshops. And those who were refraining from organised fun were enthusiastically dancing, enjoying being able to spend time with people like themselves.

She pointed at the rainbow flag and asked me what the event was about. I told her that it was a sports tournament held mostly by people who were homosexuals and transgenders, upon which she said: “I am a lesbian too”. She said it so genuinely that it sounded like the most natural thing in the world. I replied that she was welcome to attend the activities and even join the mixed team if she wanted. She was joyfully smiling as she left the stand. I am sure she will never forget that day, that crowd and the experience of seeing all the different expressions of gender together in the same space.

Queer Olympix has demonstrated the resiliency of the LGBTI+ community in Turkey. It is eliminating barriers to practice sport. But it is also telling the world that queers will not be excluded from public space. We may face restrictions. Political and social repression may prevent LGBTI+ groups from staging marches and celebrating Pride. But if we are not allowed to walk, we will aspire to run.

Photo caption: The second edition of Queer Olympix was staged between August 10 and 12 in Istanbul.”[:]